STRAY, 2x3.

Frame 313

From the start the film had something to do with JFK. With the headshot. The final crack during the serene ride. Beside Jackie.

I started cruising the web for the footage. First came the JFK photos, castings, diagrams. Then came the horrific conspiracy narratives, the body heat-based images of the hidden shooter on the grassy knoll. The rifle. This was the first time I had a sense of the rifle. What form it truly took. The Coke can-sized muzzle silencer suspended by the long, narrow barrel. The thick scope.

Finally I found the Zapruder film, something I had only a vague memory of from Oliver Stone's JFK. "Back and to the right, back and to the right." As it unfolded frame by frame, I was mystified. The impending doom. The shielding, shading signage carving off precious slices of time, important clues perhaps. The sprocket holes.

And there it is, the first shot. The throat. Through walls of neck and chest muscle. The arms lose precise control, and the elbows flare out. JFK's elbows flailed pitifully like the limbs of animals midslaughter, boxers en route to the mat, fish curling on the deck. And then, as Jackie gets dreadfully close, CRACK. SPRAY. The bolt through the cow's skull. The punch as he's going down. The handle-deep knife cleaning the fish.

This happens on frame 313.

The Diagram of Oppositions

"He is the Triune Godhead. He is Three in One."

3, 1. Two numbers.

3, 1, 3. Only two unique numbers (3 and 1). And two instances of 3. 1 between two 3s--or "1 in 3s" the opposite of "3 in 1".

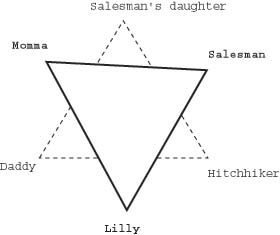

Very early in the origination of this film I developed a diagram to help me write the story. It looked like the Star of David.

The three primary characters form the foreground triangle. And immediately across from each foreground character sits a shadow character, forming a point on the shadow triangle. Often the shadow character informs the relationship of the two primary characters who surround it in the diagram. For example, between the Salesman and Momma is the shadow character of the Salesman's lost daughter. In the film he says, "You're lucky to have her (Lilly). God took my daughter away." He says this to Momma as we see Lilly. He speaks intimately with Momma, whose sexual attraction may imply a new life, a new daughter.

2 and 3

For me, the most fruitful tool during the production of STRAY was my superimposition of the duality over the Trinity. Twos and threes. The Star of David diagram shows the most explicit duality of the Trinity, a concrete Mayan calendar-like guide to the overall plot and character architecture.

For our foreground family, 3=The Trinity, but by shifting one character (e.g. Daddy for the Salesman) the story creates two families where there was one. A duality*. (* "There are opposites, but the opposites reside in the head of man. In the Godhead, the thing itself may be its own opposite.") A fertile dual life creates or implies a designed duality in the place of questionable ambiguities. During the production, if a seeming ambiguity arose I strove to force it, not into monastic clarity, but back toward an organic, healthy duality.

Star of David families.

Daddy and the Trinity

Origin of Daddy: After the first 18 hour evening shoot Eleanor, my 11-year-old star playing Lilly, had gone supernova. The next day a call came from her father 30 minutes after her call time: she's in bed, she doesn't want to get up, she doesn't want to make this movie, and she may never want to make another movie again. Somehow this forced me to think: "He's right. I really do need another character." I drove home to get my jeans, wrote a song on the way for the scene I was inventing, came back, shot it-with the song-and emerged from the set to see Eleanor at craft service. She was ready for her monologue by this time and did very well that day.

Personnel Imperatives: Maria, Eleanor, and Johnny Dowd

Producer: Maria Mallon and I were introduced in a cafe. Tall, dark. Disarming and harsh. A direct LA approach that sent locals running for cover. The day before our first car sequences we suddenly had no car, Maria went running through town with "Your car is beautiful! Let's put it in a movie!" fliers. I knew that STRAY was going to make it into the can. Tenacious and with long lasting energy, she adopted the film and all the film's orphans--fed them, gave them some tough love, etc. Her boundless energy.

Lilly: Eleanor Holzbaur-Ritter came into the same cafe in Ithaca, NY where I had met Maria. Toothy smile, short for her age, light coloring, beautiful eyes. She was a pro; she handed me 2 or 3 video cassettes, and we talked. She later read with Maria--Maria's a friend of her family--Maria and I spoke, and it was on. Somehow we found the perfect Lilly without a casting call. Salesman and Momma weren't as easy to find.

Music: Johnny Dowd. I was having a difficult week. The funding for my office at Cornell had just been cut, but even worse, in the middle of a mediocre Friday night restaurant I get a call from the artist who had agreed to score STRAY.

"Hey Thomas... Hi, hey man I'm really sorry, but I've been thinking, and I'm sorry I haven't called you earlier, but I've been thinking about the music for this movie and I just can't--I just can't do it..." And then, trailing off into the air of our breakup... "I can recommend some folks: there's this guy who does some lyrics-based stuff, it's very dark and kinda, well, humorous. Name is Johnny Dowd."

"Okay, thanks, bye."

That weekend I picked myself up, knowing I had already lost one month, and went to find this music. Lyrics-based and humorous? Hmmmphf.

One year later, nearly, and I can't believe that I know Johnny Dowd. And that his music is in STRAY. Something I couldn't foresee.

Storyboards and the Look of STRAY

Color correction and the trailers. I did many things backwards on this film, as it was by far my most in depth video project. So when I saw it on an NTSC monitor for the first time, gearing up for continuity color correction, I was horrified. I had been editing the film in Final Cut Pro on computer monitors that had lulled me into complacent satisfaction. On NTSC monitors, both decent and indecent, the greens became washed out, translucent. The blacks were grey and muddy. The frame rate, refresh rate, made what had been smooth look jumpy, amateurish.

I had just spent over a year making a DR WHO episode.

First came the color correction for Trailer 01. I cut it together and then put it into a "look vise", a trash compactor. I had nothing to lose. I started by draining the color almost completely from the driving sequences--and by blurring the image slightly to remove the video flicker. By in effect erasing parts of the image I was starting to get somewhere. And again, since it was the trailer, the pressure was off. The first trailer held together and I showed it to Ron Rice. I didn't know if I had panicked and jumped to trash the film--or if it was working the way I wanted it to. Thankfully, Ron got it.

So I jumped in to adapt the rest of the film, breaking down the visual structure into 26 color families or sections.

For something larger than the trailers I needed a guiding principle, or two. The first was efficiency: I had chopped out sections of evangelist monologues to focus the viewer's attention, and I was going to approach the color correction the same way. I brought the readability of the overall image down. My focus would be to degrade the image until only the critical elements of each frame were visible.

The graphic connection I made brought the picture full circle. This principle of efficiency of image reminded me of the work I had done a year and a half earlier on the storyboards. A tight timeline and limited drawing experience led me to develop a very minimalist style for the drawings I made for STRAY. Yet the drawings were compelling. And now, I could make the video images reflect the clarity of these storyboard images.

Thomas Richardson

TR 2004